Three years after its failed bid at a merger with Cleveland, the poorest city in the state of Ohio ventures a comeback

EAST CLEVELAND — After dropping off a “wet one” (a man high on PCP) at University Hospitals Emergency Room, the ambulance pulled northeast onto Euclid Avenue near Cleveland’s border with East Cleveland.

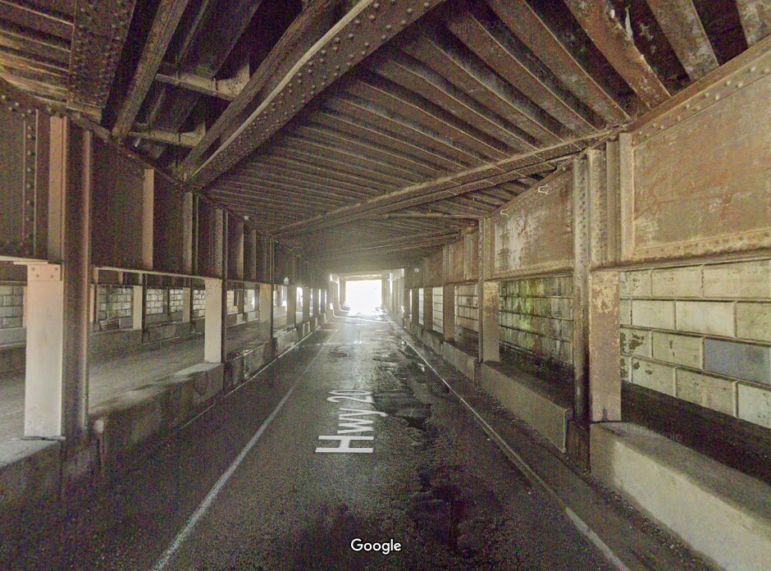

The mirror-finish of The Museum of Contemporary Art reflected trees in full summer bloom as the two East Cleveland firefighters made their way back to their engine house. They cruised by fast-casual restaurants in gleaming new buildings and the Case Western Reserve University Bookstore and the Cleveland Institute of Art building named for George Gund — the mid-20th-century Cleveland banker and philanthropist — before barreling under the concrete and wrought iron railroad bridge that separates Cleveland’s booming University Circle neighborhood from the broken-down streets of East Cleveland.

“The scenery sure does change,” said Kyle Soca, the rookie piloting the squad, as the bridge shrank in the rearview mirror and the sidewalks became populated with boarded up storefronts and crumbling apartment buildings.

State Sen. Kenny Yuko, who represents both sides of the bridge in the Ohio legislature, stated it more bluntly. “You go east, underneath that god-ugly bridge,” he said, “and all of a sudden you go from Shangri-La into East Cleveland, and you look around and you go, ‘My god, what happened? Looks like a bomb went off here.’”

What happened is a common refrain in communities like East Cleveland across the United States: redlining and block-busting and white flight and black flight and deindustrialization and the subprime mortgage crisis. A toxic stew that simmered for 50 years.

But the difference between East Cleveland and the distressed neighborhoods of Cleveland is that East Cleveland — all 3.2 square miles of it — is a city unto itself without a booming neighborhood like University Circle.

Map Credit: Cid Standifer/Cleveland Plain Dealer

East Cleveland’s tax base has been devastated by depopulation (down to near 17,000 people from a high of near 40,000 in 1970), the loss of jobs and income tax (see the decimation of GE Lighting and the shuttering of Huron Hospital), a poverty rate above 40 percent and a median household income of just $21,184. As a result, city leaders are forced to operate on a general fund of about $10 million. That’s less than $600 per resident.

Compare that to neighboring Cleveland, where the general fund is more than $651 million, nearly $1,700 per resident. Selma, Ala., which has similar numbers for poverty rate, median household income, and population, has an operating budget of $17.8 million. It seems the only category in which East Cleveland outperforms the civil rights capital is in its African-American population, which exceeds Selma’s by more than 10 points with 91.5 percent — part of a legacy of redlining practices and subprime mortgage lenders, among other things, that explicitly targeted black communities.

“What we need to do is tear down all those vacant commercial and industrial buildings on Euclid Avenue and make them shovel-ready so that we can get some economic development happening,” said Yuko, who will soon introduce a bill to the Ohio legislature that would allocate $50 million state-wide to such efforts. “Because right now, I can’t bring a developer here and tell them, ‘You know, I envision a brand new building and 100 employees running in and out of the parking lot at the beginning and end of the work day.’ They’d say, ‘What are you, smokin’ weed or something? This place is a nightmare. No one’s gonna buy this.’”

Nevertheless, Yuko and East Cleveland leaders hope that the ongoing development at University Circle has nowhere to expand but up Euclid Avenue. In the meantime, a 2016 attempt at a merger with Cleveland is now a memory and with no bailout forthcoming from the state, city leaders are forced to get creative with the meager resources available.

At the engine house on Marloes Avenue, which still has grooves in the concrete floor for the wooden wheels of bygone fire trucks, East Cleveland Fire Chief Mike Celiga checked in with Soca, the ambulance driver, and the rest of C-Shift on the recent switch to the county dispatching service. The move is one of the ways the city is saving money: upwards of $100,000 over the next three years.

The adjustment has been rough but it’s more or less working. Even so, there are groans amongst the rank-and-file over the loss of roughly $750 a year, per man, in self-dispatching pay. (There will also be savings from the police department, in salaries for dedicated in-house dispatchers who will no longer be needed.) It may seem like nickels, but these are the lowest paid firefighters in Ohio. Their compensation ranges from $10.40 an hour to just $62,000 annually for the chief. The loss of $750 feels like a kick in the teeth.

“Next guy who eyerolls me I’m gonna snap!” Celiga yelled at his deputy chief, Geoffrey Walton, after the nine disgruntled firefighters of C-Shift dispersed.

Graph by Joel Downey/Cleveland Plain Dealer

Chief Celiga understands their frustration: No one in the department, including him, has gotten a cost of living raise in seven years. But his guys, especially the veterans who’ve been doing the eye rolling, should know that there’s little he and the mayoral administration can do while the city’s under fiscal watch by the State Auditor’s office and there are other needs the city must address, like paving roads and erecting streetlights — basic city services that other municipalities take for granted.

In his office on the second floor, Chief Celiga offered a litany of complaints: Out of the nine guys on duty, four are rookies barely old enough to drink, with Soca only two years removed from high school. Too many 20-year-olds, said the chief, both firefighters and equipment, including engines and squads notorious for breaking down in the middle of Euclid Avenue, and too little pay to keep guys from fleeing to other departments.

The chief also has plans, like opening up a public health clinic in the engine house. The idea is to not just improve the health of the community but to lessen the burden on his under-resourced department, which transports too many uninsured and destitute residents to the ER for ailments that could easily be prevented or treated elsewhere. The department bills out $800 per ambulance run, but 60 percent goes uncollected to the tune of $1.4 million annually in uncollected revenues. A health clinic, said the chief, would spare his equipment the wear and tear of East Cleveland streets, which can lessen the lifespan of a vehicle by tens of thousands of miles. But in a cash-strapped city like East Cleveland, the funds for a health clinic are difficult to come by.

“What’s the rainy day fund at for the state?” the chief asked, referring to the state fiscal emergency fund that Gov. John Kasich started building in 2011 in part by gutting the Local Government Fund. For East Cleveland, that’s meant a reduction in state aid from $3 million a year to $1.75 million annually. “Last I heard the rainy day fund was in the billions. Well it’s pouring in East Cleveland. Where’s the money?”

Graph by Joel Downey/Cleveland Plain Dealer

On a pleasant summer evening in early August, Rick Martin had a bone to pick when he joined a Neighborhood Group 2 happening in a vacant lot on Milan Avenue, “down the hill,” as they say, in the valley north of Euclid Avenue.

“Streetlights on 133rd,” said Martin as he took a seat amongst his neighbors on the red and black garden furniture.

Martin, a man in his middle 50s wearing a flat cap and chewing on a toothpick, lives at E.133rd and Milan. His friend and neighbor, a middle-aged man in a red T-shirt and baggy jeans, accompanied Martin to complain about the missing streetlights.

“It’s pitch black,” the friend said. “I’m scared for my life at nighttime.”

The difference between Neighborhood Group 2 and most organized block clubs in other cities is that Martin and his friend were directly addressing the mayor and his chief of staff. They had come to talk to the residents about the specific needs of their seven-block slice of the city: abandoned houses; overgrown vacant lots; potholes; dead or dying trees; groundhog population; and, yes, streetlights. It could be worse. Neighborhood 9, which covers the area northwest and southwest of Nela Park, included on their list of concerns blocks plagued by prostitution, drug dealing, and illegal dumping.

There are 13 such neighborhood groups in the city. That includes relatively well-off Forest Hill, with its French Norman–style Rockefeller homes. But its location up the hill has proven too remote for any of its prosperity to trickle down to the city at large; and the neighborhood’s assets are not big enough to make up for the overwhelming poverty in the valley below.

Slide the bar above to compare homes on Milan Ave. and Hartford Rd. between Claiborne Rd. and E 133rd St. in 2010 (left) and 2019 (right). In that time period, 13 buildings were demolished.

Map Credit: Cid Standifer/Cleveland Plain Dealer

In the two years that Neighborhood Group 2 has been in existence it has worked closely with the administration to help direct upwards of $400,000 of government funds. The very lot where the group was meeting featured a dilapidated blue-and-white up-and-down double covered in wild ivy only last year, and was known as a center for drugs and prostitution. It was among five on this block chosen for demolition by Hank Smith, a 67-year-old resident of Milan Avenue and a leader of Neighborhood Group 2.

“Hank done changed the very structure of this street,” Mike Smedley, chief of staff at East Cleveland City Hall, said earlier in the meeting.

The mayor, Brandon King, an East Cleveland native and graduate of Shaw High School (class of 1986), leaned forward in his black garden chair with a head full of locs running down the length of his back and addressed Martin’s concern about the lack of streetlights at 133rd and Milan.

“We are challenged with streetlights,” said the mayor, sharing the man’s frustration. “They [reckless drivers] knock ’em down as fast as we put ’em up. We’re out of poles, we’re out of bulbs, we’re out of arms.”

The mayor, who has a laid-back demeanor and the deliberate cadences of a born salesman, then offered Martin and the group a disquisition on how East Cleveland acquires streetlights. “You cannot just go to Silverman’s and buy one,” he explained, adding that they must be manufactured, or made to order. Because of East Cleveland’s fiscal troubles, he went on, the city relies on federal grant money for streetlights. When petitioning for such funding from the federal government, you must provide three bids from licensed contractors. If only one bid comes back — which is often the case with streetlights — you must bid the contract out a second time. If again only one bid comes back you must then petition the federal government to accept it.

“It’s a process that’s gonna take 12 weeks,” said the mayor. “All I can do is ask you to be patient.”

Martin and his friend complained that their sidewalks had been dark for more than a year. The mayor cited a streetlight that he’d replaced within the last 12 months at the corner of 133rd and Milan, only to be quickly knocked down again. A heated back and forth ensued with Martin turning to the issue of potholes as further evidence of King’s inaction.

“We patched up our own street,” Martin said. “Y’all didn’t do that; we did!”

“Okay, where did you get the cold patch?” the mayor retorted. “I dropped off the cold patch.”

“It’s not my job to patch up my street!” replied Martin.

“Hello!” interrupted the group’s president, Shirley Hatcher, a stylish 70-year-old with maroon-dyed hair. “We got to be the village, we need to work together to do whatever needs to be done. The city doesn’t have all that so if we get the cold patch, if we can do something to fill in, why not?”

The residents used the episode as an opportunity to cite what they had accomplished by working closely with the mayor. They spoke of cataloging and prioritizing various concerns on seven streets and of directing various government funds to meet some of those needs. Additionally, residents said that by having a stake in the city beyond their personal property lines they were now inspired to mow vacant lots, keep an eye out for illegal dumpers, and, yes, even fill potholes with cold patch dropped off by the city.

Earlier in the summer, in his wood-paneled office in City Hall, King said the neighborhood groups were both helping him govern and giving the citizens a stake and a sense of pride in their community.

“I go to these groups and I say, look, here’s our annual budget,” said the mayor. “Out of the $10 million, $6 million automatically goes to police and fire. Out of what we have left, I’ll spread this around so that everybody gets something.”

When the citizens play a role in directing funds, he said, they become more prudent in how to meet their needs and more understanding of the challenges of the city. The mayor then gave the example of having $40,000 in demolition money to spend on a block and a neighborhood group having to decide between demo’ing four blighted houses (at a cost of $10,000 apiece) or razing a four-suite apartment building (at a total cost of $40,000). The four-suite apartment building may be of more concern to some residents, said the mayor, but, as a group, once they’re informed of the costs and the limits of the demolition budget they inevitably decide on the greater impact of demolishing the four houses.

“It’s beautiful because you get the person who lives next door to the apartment building, they want it down,” said the mayor. “They come complaining, and our answer is democracy led to this.”

King said that last year the groups spent a combined $1 million and that by the end of this year they will have spent upwards of $3 million. “It’s their money,” he said. “Somebody called it returning democracy to the people.”

On Milan Avenue at the Neighborhood Group 2 meeting in early August, Shirley Hatcher summed up her feelings about the program: “I like this power,” she said, as she looked over the top of her tinted lenses directly into the eyes of the mayor.

As a matter of policy, administration officials will not disclose the exact number of East Cleveland police officers for fear the low number will inspire those who wish to commit crimes. East Cleveland Police Chief Michael Cardilli will only say “it’s above 40” in a city where the lawbook states he’s to have 72.

“When I started as police chief in 2014 my budget was about $5 million,” said the chief, who has a total of 22 years in the department. “It’s $2.8 million now.”

In a city divided into four zones, Cardilli said he still has two cars per zone, but where he used to have a sergeant for every zone, he now only has one.

“The sergeant is running the shift and I don’t have the lieutenants,” said Cardilli, who in addition to having fewer supervisors is also dealing with a majority of officers who have less than three years of experience — a result of being the lowest paid police department in the state of Ohio. The trick, said the chief, is “work smarter.”

For Sgt. Larry McDonald — who Cardilli referred to as “my right-hand man” — working smarter appears to mean compensating for the department’s low numbers with outsized attitude and presence. Or, as McDonald called it, a proactive form of policing meant to deter crime by simply “letting people see that we’re out here.”

Earlier this summer, in a vacant lot behind the Family Dollar on Euclid, McDonald gathered six patrolmen and laid out a strategy for the shift.

“We’re getting ready to saturate the community,” the sergeant told the patrolmen, who surrounded their supervising officer in a semi-circle. “Remember like last time? We’re checking everybody. Everybody that’s a nuisance is everybody gets checked.”

The 12-year veteran of the East Cleveland Police Department then named a handful of “trouble spots.”

“We’re gonna first hit Plymouth,” said the sergeant. “Remember how we did Plymouth? Whoever’s sitting in their car we’re stopping the car but letting enough room for the next one to go around. Then we go from Plymouth to Sam’s Deli. We’ll hit 137. And then we’ll circle back around and do our hoes. Get them off for the day.”

Less than five minutes later, McDonald’s police cruiser pulled hard and quick onto Plymouth Place before coming to an abrupt halt behind two patrolmen conducting a routine traffic stop for a trivial infraction, just as described in the huddle. The sergeant hopped out with an aggressive posture and stared down the bystanders on the sidewalks and porches of this small side street of 16 doubles and duplexes, half of which were vacant and abandoned. Two more police cruisers pulled onto the block, for a total of seven officers.

For more than two minutes, the sergeant and his hard chargers mulled about in the middle of Plymouth Place with their hands menacingly resting on their utility belts. A gospel dirge played on a portable radio as a man in his driveway working on his car tried his best to ignore the display; a young man in a white tank and sweatpants held up his smartphone to document the scene in case something popped off; a weather-beaten Cleveland Cavaliers flag hung upside-down in a second-story porch; and a man in a blue ball cap and goatee stood limply on the sidewalk, a stunned and frightened expression on his face as McDonald ambled nearby.

The traffic stop completed, the sergeant nodded to the patrolmen and just like that they all got in their police cruisers and left.

“You always want the community to see you out here working, because the people who are doing wrong are also gonna see you and they’re not gonna want to be around,” said McDonald as the police cruiser departed Plymouth. “People don’t see the police being proactive, crimes start to be committed.”

Like the force as a whole, McDonald is not physically intimidating: 5-foot-9; not a gym guy; 42 years old and starting to show it. But he’s the last person you want to confront in East Cleveland, where he’s known on the street as Pac-Man for eating up everything in his path. The slightest hint of noncompliance and Pac-Man is in your face and barking, threatening jail for you and anyone else you’re connected to.

Earlier in the afternoon, the sergeant’s appetite extended to private property: On Roxford Road, a porchful of men were told that if the front yard wasn’t cleaned up of debris and garbage in 24 hours, “I’m gonna run everybody on your porch, and I’m gonna arrest whoever I can. We gonna have order on this street.” Later in the afternoon, on Gainsboro Avenue, a similar threat was made over a truck parked in the front yard: “You have 24 hours to get all that in the back and on the side cleaned up. If not, I’m coming with tow trucks. Any vehicle without a license plate on it.”

“But it’s in the backyard,” said a man on the porch of the collection of scrapped cars.

“If I can see it from the driveway, it belongs to me!” barked McDonald.

On Elwood Road, in front of a vacant and abandoned house known by police for attracting trouble (“drinking, drugs, fighting and guns”), McDonald’s radical version of Broken Windows policing came to a head when he came upon two teenagers hanging out on the sidewalk, or, as the sergeant saw it, engaged in the crime of loitering.

“I ain’t done nothin’, bruh,” said Aaron, an 18-year-old who just graduated from Shaw.

“I’m not your bro,” said McDonald, as he chicken-winged Aaron’s right arm behind his back, forced the teen face-forward onto the hood of the police cruiser, placed him in handcuffs and then put him in the back of his car. “We told y’all time for time this is not your house … you gettin’ ready to take a ride to the jail.”

Aaron continued to plea that he’d committed no crimes, to which McDonald replied that he had, citing the charge of loitering. It was a lecture both for the two teens in custody as well as those watching from their porches.

“Did I call y’all?” asked a woman from her porch, wanting her neighbors to know that she wasn’t responsible for the police disturbance.

“Somebody should be calling,” McDonald yelled into the air. “One of these stray bullets hit one of y’all innocent people’s kids then we gonna have all kind of teddy bears and white t-shirts. Somebody should be calling!”

There is logic to McDonald’s approach: The house the two teens were in front of, according to the sergeant, had been at the center of a lot of gun calls. But at least one policing expert is troubled by such tactics.

“When police approach the community aggressively — when they come at the job of policing like an occupying army — it may reduce crime in the short-term, but there’s a high potential that it will increase crime in the long-term,” said Seth Stoughton, a University of South Carolina law professor and former officer who writes extensively about police regulation and use of force.

The professor cited three ways in which McDonald’s aggressive style of policing can lead to a higher crime rate: 1. If officers are making arrests for nonviolent misdemeanor offenses, there’s more people with criminal records, which means more people having trouble getting legal employment who then turn to illegal employment. 2. If community members believe officers are exercising their authority illegitimately, they are less likely to obey the law, comply with police, or seek help from police when they need it. 3. When a community feels alienated by police, they’re less inclined to cooperate with police investigations.

Stoughton also said that Aaron’s detainment might have been a violation of the Fourth Amendment, which guarantees “The right of the people to be secure in their persons.”

Police tactics have been costly to the city, most recently a $50 million payout to Arnold Black in a high profile police brutality case.

As Aaron sat handcuffed in the back of the police cruiser for upwards of 35 minutes, the teenager spoke about his relationship with the sergeant, who he knows from the policeman’s time as a resource officer in East Cleveland Schools.

“I really think he thinks I’m like a criminal,” said Aaron.

“He’s a good officer,” the teen said when asked. “I guess he wants to keep me out of trouble or something. But I didn’t think you could do all this for just standing outside.”

Aaron’s friend, who sat cuffed and detained in the back of a separate police cruiser, was less forgiving of McDonald. “Who to arrest them?” asked the 19-year-old. “Who to tell them they ain’t supposed to do that? Who to tell them they’re wrong?”

At Aaron’s Aug. 1 court date, the prosecutor, public defender, and judge appeared well acquainted with McDonald’s style of policing.

“Once he knows you and once this happens, he’s gonna give you a summons every single time,” East Cleveland Prosecutor Heather McCollough told Aaron before the judge commenced the afternoon session. “Every single time. Every. Single. Time. Every … single … time.”

“I think he gets it,” said the public defender, Zach Humphrey, as both sides of the courtroom were now rolling their eyes in exasperation at the lifetime of attention Aaron could now expect from McDonald.

East Cleveland Municipal Court Judge William Dawson appeared to acknowledge the young man’s predicament, knowingly smiling and nodding his head when the prosecutor informed him that she was letting Aaron off with a warning that “he has been noticed by a particular officer known to cite people that he recognizes for hanging around on sidewalks and things of that nature.”

The public defender’s opinion: “It’s a public sidewalk, so I’m not exactly sure what law he was breaking,” said Humphrey.

Three years ago, when the idea of Cleveland annexing East Cleveland was being considered, Hank Smith, who would later become one of the founding members of Neighborhood Group 2, was undecided.

“It had a lot to do with pride — this city has been black run for a long time now,” Smith, an African American and a resident of East Cleveland for 43 years, said recently after a meeting of Neighborhood Group 9 on Noble Road. “And ever since it’s been black run, it has been going down hill, and I just didn’t want to see the city fail.”

Smith understood the benefits of annexation: more police with the requisite oversight, more streetlights, a snow-plowed path in winter from his home on Milan Avenue to the major throughway of Euclid, and perhaps some economic development resources that could bring new businesses to the area. But Smith feared that annexation would not just be seen as a failure of East Cleveland, but a failure of black government. He did not want the final analysis to be that black people can’t govern themselves.

“And that bothered me a lot,” said Smith, whose opinion is shared by many East Cleveland residents, evidenced by the recall in a late 2016 special election of East Cleveland Mayor Gary Norton, who at the time was leading the annexation effort.

The story of East Cleveland’s troubles includes mismanagement by city leaders. In 2012, the state declared East Cleveland to be in Fiscal Emergency after the city was found to be carrying a deficit in excess of $5.8 million. The city was simply spending more money than it was bringing in. And while East Cleveland has made great strides since then (it ended 2018 in the black largely by obtaining federal grants to subsidize police and fire) the city remains in Fiscal Emergency, which means continued scrutiny by the State Auditor and the Office of Budget and Management, state-forced implementation of austerity measures, and no bond rating or ability to take on new debt. (At a recent meeting of the State Fiscal Planning and Supervision Commission, King was practically begging the commission to allow him to lease some salt trucks for the coming winter.)

But local experts who study the impact of housing policy on Cuyahoga County say the social and economic forces of the last 50 years — from block-busting to the subprime mortgage crisis — far outweigh any mismanagement by city leaders when it comes to placing blame for the crisis facing East Cleveland.

“The problem of looking at East Cleveland as a failure of city leadership is it lets everybody else off the hook,” said Frank Ford, senior policy advisor for the Western Reserve Land Conservancy and a leading expert on urban disinvestment.

When a city loses half its population and half its tax revenues within the span of a generation, the problem becomes greater than the purview of city government, said Ford.

“We shouldn’t forget the fact that there’s decades of housing policy and certainly the subprime lending crisis that play a major role in all this,” said Ford, whose recent study on housing trends in Cuyahoga County shows how African-American communities were explicitly targeted and negatively impacted by subprime mortgage lenders, who left blocks upon blocks of blight in their wake. With an estimated 510 vacant and abandoned houses as of February of this year, East Cleveland had 210 more homes in need of demolition than the rest of Cuyahoga County suburbs combined.

Thomas Bier, a former director of Cleveland State University’s Center for Housing Research and Policy, and a leading expert on urban sprawl and urban development, places the blame for East Cleveland on the state. But it’s not just a matter of inaction or the reduction of Local Government Fund monies. “The state is shifting economic strength from the city of Cleveland and its inner-ring suburbs to the exurbs,” he said.

Bier pointed to such state-funded projects as the widening of Interstate 271 where the highway meets I-480 in the southeastern part of Cuyahoga County. As a result of the Ohio Department of Transportation pouring money into exurban infrastructure, explained Bier, exurban communities like Solon get stronger and new exurban communities with low tax rates get developed, which pulls population — and economic strength — from inner-ring suburbs. As those inner-ring suburbs get weaker, in the form of declining property values and market rents, it spells more flight from East Cleveland into its neighboring suburbs.

“It’s a pyramid scheme,” said Bier. “The core will collapse and that collapse will follow the growth.”

What Bier would like to see is for the state to stop doing any sort of investment that would promote the development of farmland. But instead of recognizing the relationship between the decline of East Cleveland and state-funded infrastructure projects like the extension of water and sewer utilities farther away from the urban core, state leaders will cite Ohio home rule law and blame the city’s fiscal crisis on mismanagement at the local level.

“If King goes down to Columbus, they’ll say your problems are your problems,” said Bier. “Here’s a cup of coffee, you know the way home.”

In addition to moving economic growth farther away from the region’s urban core, state leaders have directly impacted East Cleveland’s fiscal health by slashing the Local Government Fund. The city’s 2012 Fiscal Emergency declaration came in the same year that the state cut its aid to the city by more than $1 million.

“They just cut it,” said Smedley, the mayor’s chief of staff, exasperated. “For other communities it may not mean a lot, but a million dollars cut out of our budget, out of a $10 million budget, that’s 10 percent.”

In particular, the cut directly resulted in laying off police, said Smedley.

And the pressure from the state keeps coming: the latest tucked into a gas tax bill, signed into law this year, that effectively bans East Cleveland and municipalities across the state from issuing fines via traffic camera programs. According to House Bill 62, for every dollar a municipality collects via photo-enforcement program a dollar is to be deducted from said municipality’s Local Government Fund aid. For East Cleveland, that could mean a loss of an additional $1 million a year in state funding if efforts to challenge the law through the courts prove unsuccessful. In a poetic twist, the city is fighting HB 62 on the grounds that it violates home rule, the very law the state uses to deny East Cleveland aid.

Despite the challenges imposed by the state — not to mention lawsuits against the police department that continue to choke city coffers — East Cleveland leaders continue to seek new ways to save and generate revenue.

There’s a plan for the city to open an impound lot that could yield an estimated net profit of $173,000 a year; the administration has committed itself to paying up to $90,000 annually (which would be the highest salary in City Hall) for an economic development manager to try and pull some of that University Circle development past the railroad bridge and up Euclid Avenue; and Northeast Ohio Alliance for Hope (a local CDC and community organizing group) is lobbying county and state lawmakers to enact policy that could help bring a quality grocery store to the food desert that is East Cleveland.

Back on Noble Road, Hank Smith continued to explain his feelings about the annexation bid three years ago. Despite his misgivings about how a merger would reflect poorly on black governance, he said at the time he was still open to it because he knew the city just couldn’t keep moving in the direction it was headed.

“But now I see some leadership that can lead us forward into the next stage,” said Smith. “Now I see an opportunity for a turnaround … and we’re still running the city.”

This story was a joint project produced by The Plain Dealer and Eye on Ohio, the Ohio Center for Investigative Journalism.