-

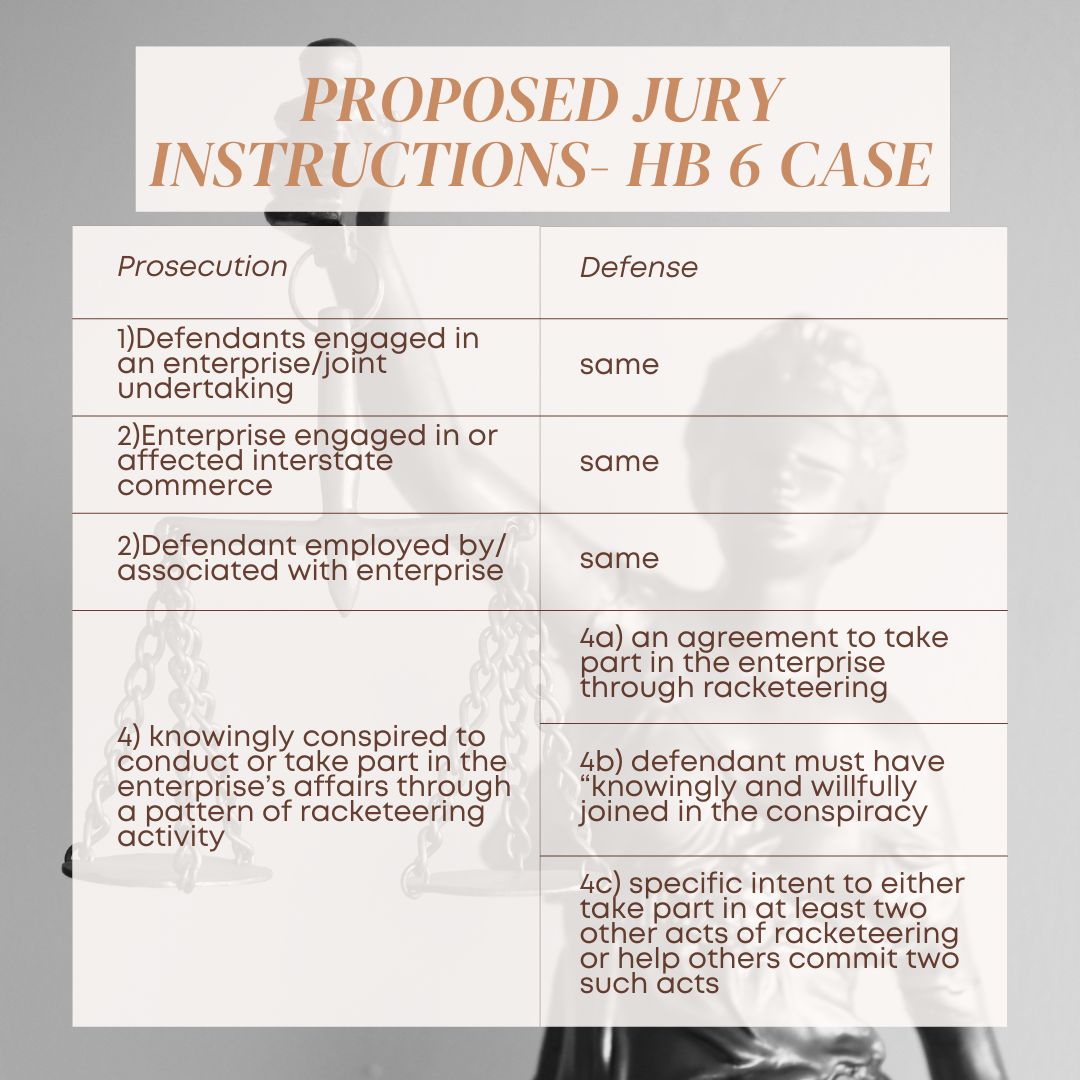

Householder seeks to sow reasonable doubt in Ohio corruption trial

The defendant in Ohio’s largest corruption case gambles by taking the stand. Whether it and other factors will counter elements of the government’s case remain to be seen. By Kathiann M. Kowalski This article is provided by Eye on Ohio, the nonprofit, nonpartisan Ohio Center for Journalism, in partnership with the nonprofit Energy News Network.…

-

Householder trial: New evidence shows depth of long-suspected scheme

By Kathiann M. Kowalski This article is provided by Eye on Ohio, the nonprofit, nonpartisan Ohio Center for Journalism, in partnership with the nonprofit Energy News Network. Please join the free mailing lists for Eye on Ohio or the Energy News Network, as this helps provide more public service reporting. Ohio’s largest corruption case continues…

-

Why attention to detail matters in the government’s HB 6 corruption trial

Opening argument last month gave a bird’s eye view of what the prosecution plans to show in its criminal case. Now the government is laying out the hundreds of puzzle pieces from which they hope jurors will see the big picture. By Kathiann M. Kowalski This article is provided by Eye on Ohio, the nonprofit,…

-

‘You Ain’t No Big Man’: Videos Show Disparities in Cleveland Police Response to Kids in Crisis

This story is a joint project of the nonprofit The Marshall Project – Cleveland and Eye on Ohio, the nonprofit, nonpartisan Ohio Center for Journalism. Please join the free mailing lists for Eye on Ohio or The Marshall Project, as this helps provide more public service reporting. By Cid Standifer An ambulance was already outside…

-

Freeze of regulator’s HB 6 cases could further harm Ohio consumers

A federal prosecutor’s move to stay PUCO cases would thwart investigations behind FirstEnergy’s spending and other matters related to Ohio’s ongoing House Bill 6 corruption scandal. This article is provided by Eye on Ohio, the nonprofit, nonpartisan Ohio Center for Journalism, in partnership with the nonprofit Energy News Network. Please join the free mailing lists…

-

Ohio Civil Rights Commission finds probable cause of disability discrimination in Dublin case

Mysterious arson remains unsolved This article provided by Eye on Ohio, the nonprofit, nonpartisan Ohio Center for Journalism in conjunction with WOSU 89.7 NPR News. Please join Eye on Ohio’s free mailing list or download the WOSU Public Media Mobile app as this helps provide more public service reporting to the community. By Lucia Walinchus…

-

Covid Correctional: behind Ohio’s campaign to get prisoners vaccinated

By Cid Standifer When James Burris was sent to quarantine in a solitary confinement cell, the doctor wouldn’t tell him who allegedly exposed him to the coronavirus, citing laws protecting personal medical information. Burris said he and the four other men sent off to quarantine with him deduced who might have exposed them by comparing…

-

Does freedom of the press extend to covering police?

Almost a year later police still won’t identify officer who attacked journalists; Reporters say they mostly work without incident but face an increase in online threats This article provided by Eye on Ohio, the nonprofit, nonpartisan Ohio Center for Journalism in partnership with the nonprofit Matter News. Please join Eye on Ohio’s free mailing list…

-

Fighting to open closed doors: how advocates stepped up efforts to help sex trafficking survivors in a world where hiding victims is easier than ever

This article is from Eye on Ohio, the nonprofit, nonpartisan Ohio Center for Journalism. Please join their free mailing list, as this helps provide more public service reporting. By Christopher Johnston For women survivors of sex trafficking struggling to make ends meet, the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated an already desperate situation. Funding programs to support…

-

Ohio clean energy foe at the forefront of key points in bailout law and ratification efforts

House Majority Floor Leader Bill Seitz called the law at the heart of an alleged corruption case “the best energy bill we ever passed.” This article provided by Eye on Ohio, the nonprofit, nonpartisan Ohio Center for Journalism in partnership with the nonprofit Energy News Network. Please join our free mailing list or the mailing…